The Divine Feminine Presence

About this Article

This article explores the divine feminine in the Zohar, one of the most influential works of Jewish mysticism. The Zohar takes readers on a journey through the sefirot—the ten emanations of the Godhead (Ein Sof), often described as the universal consciousness.

I highlight how these emanations embody both masculine and feminine energies, showing the essential role of the Shekinah, the divine feminine presence, in shaping human consciousness. The mystical union of these energies not only deepens our understanding of God as pure consciousness, but also invites us to see how spiritual growth and divine encounter can help us rise above worldly suffering and move closer to wholeness.

Initially published in Omnino – Volume 12 by vsuenglish – Issuu in January 2022.

ystical language of the Zohar takes the reader on an eschatological journey of the soul, using allegorical anecdotes to describe the ten sefirot which emanate from the infinite Godhead who is referred to as Ein Sof. The mystical language of the Zohar uses symbols and metaphors throughout its text to romanticize the sacred connection of the divine masculine and feminine energies and their relationship to the human soul. While the Zohar is regarded by many as a revered collection of mystical Commentary, the authorship of the Zohar has remained a central focus of debate among scholars for some time. I will begin by addressing the early circulation of the content, which would come to be known as the Zohar, and evaluate both sides of the debate for authorship.

I intend to describe how the Zohar takes the reader on a mystical journey of the sefirot, the ten emanations of the Godhead (Ein Sof), who is described as the universal consciousness of all beings. I believe this dynamic of the sefirot offers a glimpse into the notion of God as pure consciousness. In addition, the romanticized mystical connection of divine masculine and feminine energies gives insight into the creation of human consciousness. I believe Zohar’s interpretation of the divine masculine and feminine encounter challenges the reader to understand God in his cosmic role as pure consciousness and demonstrates how vital Shekinah’s divine feminine presence is for humanity. In understanding the significance of meditations on the sefirot, the reader of the Zohar comes to understand that human consciousness can overcome the anguish of worldly experiences and accelerate the evolution of human consciousness by striving for spiritual growth and divine encounter with Ein Sof.

Authorship of the Zohar

According to tradition, Moses de León, known in Hebrew as Moshe ben Shem-Tov, was a Spanish rabbi and kabbalist that began circulating booklets to his friends and fellow kabbalists under the pretense that the book contained ancient teachings and midrash’s that had been copied from an ancient book of wisdom written by Rabbi Shim’on, ben Yohai, a famous teacher of the second century who lived in the land of Israel. Rabbi Shim’on, who spent twelve years secluded in a cave where he studied Torah, was believed to be one of the holiest sages of his day. Moses de León alleged that the ancient sage had written the book he was coping from while he was in the cave and that it had been handed down secretly from master to disciple after the rabbis’ death.

The manuscript quickly gained distinguished notoriety and may have likely never been the subject of debate; however, in 1291 C.E., when the Mamluks conquered the city of Acre in Isreal and massacred most of the Jewish and Christian inhabitants, a man named Isaac ben Samuel, managed to escape and made his way to Spain. With Isaac being from Israel, he was suspicious because he had never heard of this ancient book. Naturally, Isaac sought to find the individual responsible for the booklets. His journey led him to Moses de León, whom he found in Valladolid. Moses de León swore to Isaac that he possessed the ancient book, saying “‘may God do so to me, and more also, if there is not at this moment in my house, where I live in Ávila, the ancient book written by Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai, and when you come to see me there, I shall show it to you” (Tishby 45).

Isaac later learned that Moses de León had passed away while he was on his way home to Ávila. When Isaac heard the news, he described himself as being “furious” and going directly to Ávila to see if anyone knew about the ancient book. Once there, Isaac befriended “a great and venerable scholar named Rabbi David de Pancorbo,” who confided to Isaac that it was “clear to him without a doubt that the Zohar was never in Rabbi Moses’ possession and in-fact has never existed” (Tishby 45). Rabbi David expressed that “Rabbi Moses was a master of the Holy Name, and whatever he wrote he wrote though its power” (Tishby 45). Rabbi David suggested that Rabbi Moses provided for his family by selling these booklets; however, as a result of Moses de León’s alleged poor spending habits, his family had been left in ruins. In what appears to have been an act of good intentions, he shared that he was responsible for arranging a proposition posed to de León’s widow after Rabbi Moses’ untimely death.

According to Rabbi David, he had Joseph de Ávila arrange for his wife to meet with the widow of Moses de León to offer their son in marriage to the daughter of de León’s widow in exchange for the ancient manuscript (Tishby 45). Allegedly de León’s wife confessed to the wife of Joseph de Ávila that her husband never had any such manuscript, explaining that she had once asked him, “Why do you say that you are copying from a book when there is no book? You are writing from your head” (Matt 4). De León’s wife believed he would have more honor by sharing with others that these were his thoughts. But he believed that his ideas would only gain traction and be taken seriously if others believed the words belonged to an ancient scribe, someone of significance. So, he attributed his writings to the late Rabbi Shim’on ben Yohai. According to Rabbi David, the wife of Joseph de Ávila then spoke separately to the daughter of Moses de León, offering the same thing, the marriage of her son and a promise that she would never want for anything. His daughter reiterated the same response that her mother had. For this reason, Rabbi David was convinced that the ancient book never existed but that de León had “written pieces for other people through the power of the Holy Name” (Tishby 46).

Isaac of Acre did not allow this one account to influence his final decision on authorship. After leaving Ávila, he met Rabbi Joseph Halevi in Talavera. When questioning him about the authorship of this alleged ancient book, Rabbi Joseph insisted that Isaac of Acre should trust that this book existed, was the work of Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai, and that it had been in the possession of Moses de León. Rabbi Joseph confided that he had reached this conclusion after testing de León (Tishby 15). To test him, he told de León that he had lost a middle section of the manuscript and asked him to replace it. De León asked him to provide the last line of the text preceding what he lost and the first line of the next page so that he could recopy the section that was lost. Once Rabbi Joseph received the recopied text, he compared the two and found no difference (Tishby 15). Thus, he concluded that de León must have the original ancient book and was not writing from his mind.

Isaac of Acre further describes departing from Talavera and entering Toledo, where he made further inquiries regarding the authorship of the alleged ancient book among the scholars and their pupils. He once again found that the people were divided in their opinions regarding the text’s authorship. However, there was an agreeance that Rabbi Joseph Halevi’s test proved nothing as de León may have had a copy of his original work that he had written from his mind (Tishby 15). He would have obviously used such a copy to make the other copies. After all, if he were willing to go to such lengths, it would only make sense that he would ensure there was no reason to doubt the authenticity of the work he was putting out by the copies not remaining consistent.

The Current Debate

For the last seven hundred years, the debate of authorship has remained a central focus among scholars and kabbalists. In my research of the current debate, I have focused on the scholarly works of Gershom Scholem, Isiah Tishby, and Elliot R Wolfson. According to Wolfson, “Scholem has been the only scholar to make a serious attempt to trace the text’s provenance to determine authorship” (Wolfson, Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “Aleynu”: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity 374). Scholem dedicated fifteen years of his life to studying the philology of the Zohar. Initially, Scholem expressed doubt that the authors of all the works were one and the same. During the fifteen years that followed his initial observation, he studied “one detail after another, analyzing the language and grammatical constructions, comparing symbols, terms, and ideas of the Zohar to those of earlier Jewish mystics” (Dan 204). After a thorough analysis of the Zohar, he determined that the Hebrew language used in the Zohar was consistent with “the spirit of medieval Hebrew, specifically the Hebrew of the thirteenth century” (Scholem 163). Scholem concluded that Rabbi Moses de León was, in fact, the sole author of the Zohar. In the current debate of Zohar’s authorship, I have found a consensus among the scholarly community that they have accepted Scholem’s conclusion.

While Wolfson acknowledges Scholem’s attempts, he maintains that “despite the scholarly consensus about this forgery, no one to date has adequately explained its authorship” (Wolfson, Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “Aleynu”: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity 375). However, he further acknowledges that “to date, no critical scholar has shown conclusively that de León was not one of the authors of the Zohar” (Wolfson, Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “Aleynu”: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity 375). Wolfson and Tishby have argued that evidence suggests that the Zohar or at least sections of it only begin to surface in the latter half of the 13th century. However, some insist that this is because the ancient book was hidden away and resurfaced during the 13th century. Whatever the truth may be, one thing is clear, at the end of the 13th century Moses de León had access to sections of what would come to be known as the Zohar.

Moses de León’s career can be divided into three distinct periods: philosophy, linguistic mysticism, and theosophy. Scholem suggests that between 1275 and 1280, before developing his theosophical writings, de León composed “the Midrash ha-Ne’elam, the earliest parts of Zoharic literature, in Guadalajara” (Wolfson, The Book of the Pomegranate 6). From 1280 until 1286, Scholem suggested that de León composed, in a “pseudo-Aramaic, the various parts of the Zohar that are unified by style, language, and a common theosophic conception of God” (Wolfson, The Book of the Pomegranate 6). And finally, Scholem believes that after 1286 de León composed several Hebrew theosophic writings under his own name.

The works of de León, which we know of by name, are the Shushan ‘Edut composed in 1286. The Sefer ha-Rimmon followed in 1287; Sefer ha-Mishqal or Sefer ha-Nefesh ha-Hakhamah in 1290; Sheqel ha-Qodesh in 1292; Mishkan ha-‘Edut and Maskiyyot Kesef in 1293. In Scholem’s view, De León’s creative literary career came to a halt in 1293, and from this time until his death in 1305, he dedicated his time and energy to making copies of the Zohar (Wolfson, The Book of the Pomegranate 7). Following Scholem’s chronology, it becomes conceivable that the sequence of compositions may be summarized in the following order: the writing of the Zohar, the writing of the Hebrew works which complement the Zohar, and the distribution of the Zohar.

An interesting alternative to Scholem’s position is that of Isiah Tishby. While Tishby accepts Scholem’s claim that “de León was the author of the Zohar, he criticizes Scholem’s chronology” (Wolfson, The Book of the Pomegranate 8). The following are the main objections raised by Tishby (qtd in. Wolfson, The Book of the Pomegranate 7):

- Most of the Zoharic passages in de León’s Hebrew theosophic writings are presented as the author’s creation rather than citations from an ancient source.

- Generally speaking, the Zoharic passages cited are sentences or small fragments of larger passages that are to be found in the Zohar itself.

- The cited Zoharic passages are often not brought as they appear in the Zohar but with significant variation.

- The Zoharic passages are sometimes brought in the name of “the commentators,” an expression inappropriate for the Talmudic period.

- In several places, de León expresses a view that is at odds with that established in the Zohar.

Tishby points out that scholars have found that in early Kabbalistic literature, there are no quotations from or reference to the Zohar, which would lead one to believe that the material had not been written. The earliest citations appear at the end of the 13th century in 1281, in the Sefer Meshal ha-Kadmoni by Rabbi Isaac ibn Avi Sahulah. Here scholars discovered “two passages that are found in their present form in a manuscript of the Zohar” (Tishby 20).

In his three-volume anthology of text, The Wisdom of the Zohar, Isiah Tishby provides extensive examples of references, questions, and quotations that align perfectly with the wording found in the Zohar. In addition, Tishby notes that while “the renowned kabbalist, Rabbi Joseph Gikatilla did not directly quote the Zohar, his work from the end of the 13th century and beginning of the 14th century indicates a heavy influence of the Zohar” (Tishby 20). Tishby points out that all of the authors from his examples are all authors who lived in Spain and were contemporaries of Moses de León. It is reasonable to conclude that he likely had personal connections with each of them. Tishby notes that there is no actual reference to the book being called the Zohar in the referenced sources. Tishby suggests that the Zohar was not a known source, nor entirely put together during the 13th century and even during the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, which he says can be concluded from the following quote:

And I, Judah, the son of the pious and perfect sage, Rabbi Jacob Hayyat, peace be upon him, tasted a little honey when I was in Spain, and my eyes were enlightened. And I determined to seek out and search for wisdom, and I went from strength to strength in order to collect whatever could be found of the aforementioned book, and I gathered a little here and a little there until I had most of what there was. And I believe with complete certainty that this was a reward for all the hardships that I suffered during the expulsion from Spain. (Tishby 21)

Tishby concluded that de León was working on his Hebrew writings, as he was simultaneously writing pseudepigraphic Zoharic passages, which he then inserted into his texts in the name of “the commentators,” “the midrash,” or “the ancients” (Tishby 24). De León’s Hebrew writings indicate that he “extensively used the Zohar, often quoting from it in a fictitious manner or by simply employing its terminology and symbolism” (Tishby 25). Wolfson supports Tishby’s theory that de León had “the bulk of the Zohar before him when composing his other theosophic writings” and believes that “he was intent on popularizing the mystical system contained therein” (Wolfson, The Book of the Pomegranate 7).

Wolfson compared De León’s theosophic works to the Commentary on Aleynu in accordance with standard sefirotic symbolism. He found a “similarity in technical terms and expressions, identical use of biblical verses to derive a certain theosophical significance and parallel ideas and motifs” (Wolfson, Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “Aleynu”: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity 386). Wolfson concludes that de León’s obvious Zoharic parallels provide further evidence that, as either an “author or editor,” at some point, he “wove his works” into the “Zohar passages,” “themes,” and “exegetical comments,” sometimes in entirely different contexts (Wolfson, Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “Aleynu”: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity 386).

In conclusion, while it remains unclear if Moses de León was an author or editor of the Zoharic works, I believe the evidence from Tishby indicates that the first of the Zoharic works were developed in the latter half of the 13th century. If the work had existed in the second century, I believe scholars would have been able to find some connection in other sources. However, since the earliest use of citation for the Zohar was not until the end of the 13th century, I am of the opinion that Moses de León plays a significant role in developing the content which came to be known as the Zohar. I agree with Scholem that de León is the author of the Zohar; however, I also agree with Tishby regarding the chronology of the works. As it relates to the sefirotic works, which we will explore more below, Wolfson’s comparison of de León’s Sefer ha-Rimmon to Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on Aleynu, it is evident that de León’s employment of the sefirotic system and the divine masculine and feminine union is unique to him as an author and the Zoharic works appear to be heavily influenced by the concepts of de León’s sefirotic system.

The Ten Divine Emanations in Kabbalah

The Zohar follows the ancient Talmudic concept of the world governed by two divine attributes, Mercy and Justice. It is centered on the contemplation of the ten divine emanations known as the sefirot[1]. In Sefer ha-Rimmon, one passage states that “all (the emanations) are alluded to in the mystery of Wisdom and are joined (to it) with a firm bond” (Wolfson, The Book of the Pomegranate 227). The sefirot comprise the divine masculine and feminine union that balances the cosmos. The ten emanations of the sefirotic system can be understoodas aspects or manifestations of the divine personality and their function in the divine world and on earth.

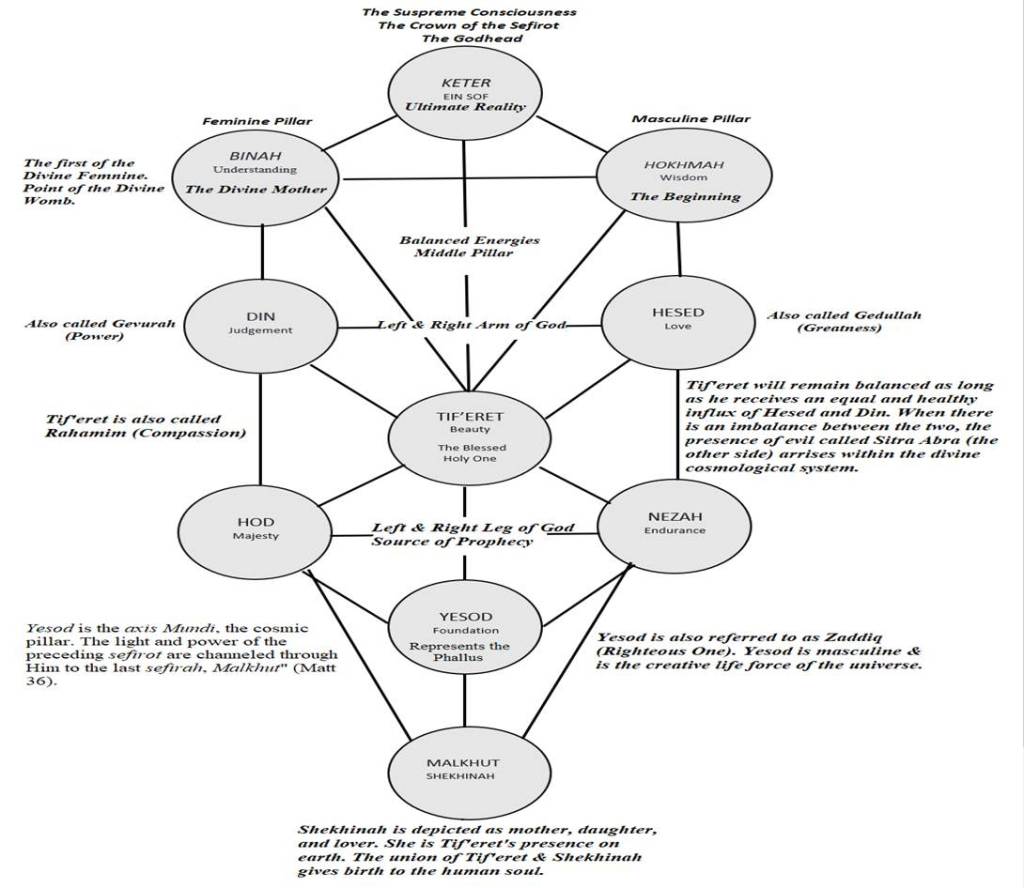

There are three pillars in the sefirotic system, the masculine is represented on the right and the feminine on the left, with the balanced energies in the middle pillar.The crown of this union, Keter, is considered the ultimate reality of the infinite God. We find the Keter is also referred to as Ein Sof, meaning nothingness, because the Godhead is inaccessible to human thoughts and understanding. It is within the Godhead that Ein Sof experiences and responds to humankind. Ein Sof is rarely mentioned in the Zohar; instead, the focus is on the manifestation of the nine sefirot that emanate from the Godhead.

“First, the primordial point of Hokhmah (Wisdom) shines forth” (Matt 34). While this is considered the second sefirot, it is actually considered the beginning because Keter, the Ein Sof, is eternal; therefore, Keter has no beginning. Thus, wisdom is the first emanation of the divine masculine. The point of Keter is the beginning of all things in the scheme of our cosmos. On the upper left, we find Binah, the first of the divine feminine, which is understanding. The Zohar describes Binah as “the place which is called life and from which life emerges” (Wolfson, Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “Aleynu”: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity 386). And in Moses de León’s theosophical works, he often refers to Binah as “the vow and the place out of which the life-force emanates” (Wolfson, Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “Aleynu“: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity 386).

Binah is the divine mother; this is the point of the divine womb. De León says in Sefer ha Rimmon, “the vow (Binah) is above every place and from there is the source of life” (Wolfson, The Book of the Pomegranate 222). She receives the seed from Hokhmah and “conceives the lower seven sefirot” (Matt 34). The divine Binah first gives birth to Hesed and Din. Hesed (Love), also called Gedullah (Greatness), is on the right divine masculine pillar of energy. And Din (Judgement),called Gevurah (Power), is on the left divine feminine pillar of energy. “They are God’s right and left arms, two sides of divine personality: free-flowing love and strict judgment, grace, and limitation” (Matt 34). Both Hesed and Din, Love and Judgement, are necessary for the world to function.

In the balance of Hesed and Din, we find the conception of Tif’eret (beauty). Tif’eret is the trunk of the sefirotic body and is also considered the Blessed Holy One, which is a common rabbinic name for God. The Tif’eret is also called Rahamim (Compassion), which is God’s emanated compassion for the world. Tif’eret remains balanced as long as he receives an equal and healthy influx of Hesed and Din, Love and Judgement.However, “if Judgementis not softened by Love, Din lashes out and threatens to destroy life. This is the origin of evil called Sitra Abra, the other side” (Matt 35-36). The presence of evil or demonic forces is birthed in the unbalanced divine cosmological system. To understand this dynamic better, one must understand the significant role of Tif’eret within the cosmos and humanity, which is revealed in Shekhinah, the tenth and final divine emanation.

Following the birth of Tif’eret, Binah next gives birth to Nezah (Endurance), the right side of the divine masculine pillar of energy, and Hod (Majesty), the left side of the divine feminine pillar of energy. These are considered the right and left leg of the sefirotic body and are the source of prophecy. The ninth emanation and middle pillar that balances the sefirot is Yesod (Foundation),representing the phallus, the procreative life force of the universe. Yesod is masculine and is referred to as Zaddiq (Righteous One), which according to the Zohar, can be seen when Proverbs 10:25 is applied to him, saying, “The righteous one is the foundation of the world.” According to the Zohar, “Yesod is the axis Mundi, the cosmic pillar. The light and power of the preceding sefirot are channeled through Him to the last sefirah, Malkhut” (Matt 36).

Malkhut is known as Shekhinah, the feminine divine of the sefirot. She is an independent being that “reflects all nine of the sefirot just as the moon, which has no light of its own, reflects the rays of the sun” (Dan 211). “In at least one passage in his Shushan Edut, de León equates the term אור הבהיר (resplendent light) with the light of the sun, in that context a symbol for Tif’eret, which illuminates the moon, i.e., Shekhinah” (Wolfson, Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “Aleynu“: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity 387). Shekhinah is both nothing and everything, depicted as mother, daughter, and lover; she is Tif’eret’s presence on earth. The Zohar emphasizes the divine union, which encompasses the romantic and sexual relationship between Tif’eret and Shekinah.

The union between Tif’eret and Shekhinah births the human soul. Shekhinah is called “the totality of all individuations” (qtd. in Matt 34). The Zohar often associates the divine energy with the idea of cosmic consciousness. Ein Sof is the infinite Godhead, the universal, unknowable consciousness of all creation. All consciousness below Ein Sof emanates from the Godhead, including Shekhinah. She is the opposite end of the Godhead, the closest divine consciousness to the created world and human beings. The human soul or consciousness birthed from Shekhinah makes herthe divine mother of all creation. I believe De León’s depiction of Shekhinah as the mother of all creation is the strength of the Zohar. It allows the human mind a glimpse into a theory of creation that suggests the human consciousness extends beyond the physical manifestations of this world. Unfortunately, he also employs the concept of division among humanity in Mishkan ha-Edut, which parallels in sections of the Zohar when he alludes to the ontological difference between Isreal and the nations. As an example, from Mishkan ha-Edut:

According to their secret and classification, all the families of the earth are divided below. Israel is the unique nation among them, existing in (a state of) holiness and in the secret of the substance of the Holy One, blessed be he (i.e., the sefirot), which is extended to them in the secret of their holy form given to them from the river that goes forth incessantly (Yesod). As there is a separation of the branches and leaves to which are attached the foxes so that the souls of the nation’s come forth from the place which is separate from that place which is the secret of holiness. (Qtd. in Wolfson, Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “Aleynu“: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity 392-393)

The Ten Emanations of the Sefirotic System

The Problem of Polarities in the Zohar

The most problematic aspect in the Zohar begins to unravel in the dynamic relationship between humanity and our impact on the union between Tif’eret and Malkhut. In the themes of the Zohar, it quickly becomes evident that the cosmic balance and essentially God, the Divine Consciousness, is dependent on humankind. “The union of the divine couple is effected by righteous actions and destroyed by sin” (Matt 24). Tif’eret and Malkhut find themselves trapped in a continuous clash between glorious unification, followed by hopeless separation. The balance of Hesed (Love) and Din (Judgement) in Tif’eret (the Blessed Holy One) determines the fate of creation at every moment.

When humans sin and invoke the need for divine judgment and punishment, it causes the entirety of the divine world to shift from Mercy to Justice, resulting in a separation of the divine male and female. Simultaneously, acts of sin and injustice strengthen the demonic energy in the lower regions of the cosmos, resulting in dire consequences. “When the powerful serpent up above is aroused by the sins of the world, it joins with the feminine Shekhinah and injects venom into Her. The Male Tif’eret separates from Her because She has been defiled” (Matt 36). The demonic sexual encounter results in souls being released from her that “are different than those issued when the sun, Zeir Anpin, was united with the moon, the Nukva” (Yohai, De León, and Berg 849).

From the position of de León, we find he correlates the nations with the demonic souls that were created. The demonic forces are “compared to the branches of the uncircumcised tree” (Wolfson, Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “Aleynu“: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity 392). The Zohar implies this further when it says, “The time of pruning has come: the time to uproot the dominion of the princes of the nations so that they will not rule over Israel when the Tabernacle is established (Yohai, De León and Berg 3:4b). And in the Commentary on Aleynu, “the nations are also compared to the branches of the tree whereas Israel is the truck of the tree or its fruit” (Wolfson, Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “Aleynu”: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity 388).

According to the sages of the Talmud, Shekhinah was present from the beginning in the Garden of Eden. We understand from the Zohar this is where Tif’eret and Shekhinah birthed souls in their image. In the Commentary on Aleynu, “the souls of the nations derive from the realm of impure forces” in contrast, “the souls of Israel derive from the Tree of Life, which in the Zohar and de Leon’s Hebrew writings corresponds to either the sixth gradation, Tif’eret or to the ninth, Yesod ” (Wolfson, Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “Aleynu“: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity 389). In Hebrew, the word Adam אדם means humankind and the word Eve חַוָּה means to breathe, to live, or to give life. Therefore, when God created Adam and Eve, it was not one man and woman alone, but rather the first generation of humankind birthed in the image of Tif’eret and Shekhinah. As we see in Genesis 5:2 where it is written, “He created them male and female, and blessed them and called them Mankind in the day they were created.”

Historically scholars have established that the first reference to the Israelite people dates back to the time of Merneptah 1213-1203 B.C.E (Mazar 234). Therefore, it is only logical to deduce that these first humans did not identify as Israelites; they were just human—humans whose consciousness was birthed from Tif’eret and Shekhinah and perhaps derived from the Tree of Life. And the souls that would come after this generation of people would also emerge from Shekhinah, the divine feminine, the mother of all human consciousness.Therefore, I believe the presence of division among nations in the text is birthed in human ignorance, holds no merit, and should not be incorporated with the concept of divine consciousness. I believe the concept of divine consciousness should embody the universal inclusion of all conscious beings, not division.

From, a logical deduction of the text, the first souls of the first generation of humans would have been birthed in perfect harmony. According to tradition, with the first and slightest act of sin, humankind disrupted the balance, creating separation and strengthening the demonic energies, which resulted in Shekhinah birthing new souls or human consciousness, whose cosmological genetics were intertwined with traces of the divine and the demonic, a new kind of soul which was capable of the greatest good, and the greatest evil. It is written, “The man has now become like one of us knowing good and evil” (Genesis 3:22). With the eschatological interplay between human nature and the disruption of the divine balance in the cosmological structure, Moses de León offers an additional theory for the problem of evil within our world.

The Garden of Eden became the first exile, and Adam, the first generation of humans, were the first to be exiled in divine punishment. The second generation of human consciousness was birthed with a genetic predisposition of divine demonic duality, which I argue is evident in the story of Cain and Abel. Biblical tradition shows God exercising extreme judgment on the future generations of humankind, indicating the imbalance of the divine system. The severe judgment and harsh punishment continue throughout ten generations from Adam to Noah, becoming more extreme, finally resulting in the intended extinction of all living things in the allegorical tale of the great flood.

Restoring the Balance

According to the Zohar, human beings are responsible for reuniting the divine couple and rebalancing the sefirot. The supreme aim of the divine masculine and feminine energies is to overcome separation and achieve complete unity. Repairing the damage “depends on humanity’s participation in the creative process” (Schmidt 108). Considering the traditional view of God’s wrath, one could reason that the generations that followed the first generation of souls were incapable of participating in the creative process to restore balance. However, in God’s search of man, He found a nation of souls to whom He entrusted this creative process. Rabbi El’azar says:

Israel is the heart of the whole world. Israel lives among the other nations as the heart among the limbs of the body. Just as the limbs cannot exist even for a moment without the heart, so all the nations cannot exist without Israel. The heart is tender and weak, yet it is the life of all the limbs. Only the heart perceives pain, trouble, and grief, for it contains life and intelligence. The other limbs are not close to the King; They have no life, they perceive nothing. (Matt 16)

God extends a pledge to Israel in the Zohar, saying, “I will place My Mishkan in your midst” (Matt 154). The word Mishkan in Hebrew is written משכן meaning the dwelling place of the Creator. He says, “My Mishkan is My Shekhinah” (Matt 154). Therefore, Shekhinah is God’s dwelling place. According to the theme of the Zohar, Shekhinah would essentially be the soulmate, twin soul, and the other half of Tif’eret. Without Her, He is incomplete, off-balance, and the world is thrown into chaos. And yet God has entrusted Shekhinah to Israel, saying, “My Mishkan is My Mashkon” (Matt 154). Mashkon inHebrew is writtenמשקון, with a slight change in spelling, producing a cholam (an o sound), the resulting word, mashkon משקון, means something that is given as a guarantee. According to the Zohar, God loves humankind so much that He gives His most precious possession, Shekhinah, as His pledge to the Israelite people, with whom He has also entrusted the secrets of the sefirot. However, God’s pledge does not come without warning; if Israel breaks His covenant through sin, He will set His face against them.

Conclusion

Shekinah symbolizes the people’s intimate connection with God. “Shekinah has often been described as the Keneset Yisra’el, the mystical Community of Israel. She prevents the masculine aspect of God from punishing Her children” (Matt 36). The souls from Shekinah are emanations of pure consciousness derived from the Godhead. Created in the image of God, our conscious experience is infinite, whereas our human experience is finite. We could reason that to be driven by desire is human nature, yet we cannot ignore the divine/demonic duality of consciousness. One could argue that every soul from the second generation forward would have been birthed in separation from Tif’eret.

It is through this dynamic that free will takes plight. When consciousness is attached to the physical form, one must choose between good and evil, the dual aspects of its fundamental nature. Therefore, it is no surprise that the covenant was broken by Israel, resulting in God turning from them as they were cast into exile, and as a result, Shekinah follows “Israel into exile” where she “hovers over Israel like a mother over her children” (Heschel 172). While Heschel describes Shekinah following her children into exile, God’s pledge to Israel and Shekinah’s love for her creation essentially acts as an exile for Shekinah, by God turning from Isreal and sending them away, she has no choice but to follow to stay close and keep them safe. “In kabbalistic thinking, the exile of the Shekhinah becomes the metaphor for understanding all forms of disharmony that affect human beings” (Leah 80).

The Talmud records a teaching from the real Shim’on ben Yohai: “Wherever Israel went in exile, Shekhinah (God’s presence) was with them” (qtd. in Leah 17). De León takes this concept of Shekhinah in exile and offers a renewed sense of hope for the Israelite people and their purpose as God’s chosen people. While Israel’s steadfast determination and dedication to God appears to be humanity’s saving grace, we must be mindful that the overall divine cosmological goal is to bring that which is above and below into perfect harmony. I cannot see how this could ever be possible considering the very nature of the souls released from Shekinah while apart from Tif’eret. Humanity severely lacks compassion, altruism, patience, forgiveness, charity, wisdom, and harmony, compared to the breeding ground for moral corruption, lying, cheating, hate, greed, envy, pride, indifference, and melancholy. According to De León, “The human being was created in the image of God so that he would strive through the way of proper knowledge to straighten the paths of his soul, for without the true knowledge the soul is lacking” (Fishbane 10).

When separated from the divine consciousness, human consciousness, in the physical state, is ignorant of the nature of divine reality and unable to comprehend the greatness of Keter. The Zohar challenges “the normal workings of consciousness,” provoking you to “examine your assumptions about traditions, God, and the self” (Matt 38). If we are created in God’s image, our creation goes beyond the physical reality, penetrating to the depths of our souls, we are part human and part divine; therefore, the key is to fight against the desires of the flesh and to enter intentionally and purposefully into the presence of the divine. In Judaism, one such practice would be Kavanah קבאנה, the Hebrew word for direction, intention, or purpose. Kavanah is a prayer for individual advancement “on the sefirotic ladder towards devekut, the state of closest proximity to God” (Schmidt 105).

While contemplation on the divine through Kavanah appears to be the answer for mending the divine union, the Zohar quickly stops its readers dead in their tracks; it places great significance on the supreme religious value of devekut in the center of its ethical system while also making it clear that such a path is reserved for those individuals who are initiated into the secrets of the sefirot, namely chosen kabbalist and mystics. However, in the modern debate, Scholem asserts, “Devekut is a starting point and not the end and is possible for everybody because God is everywhere” (qtd. in Schmidt 108). Scholem corrects Moses de León’s vital flaw by reassuring humanity that “God is all in all and there is nothing but him” (Scholem 341).

The Zohar says that the Torah comes from God, her words and letters are permeated with God, and the study of the Torah springs forth revelation. It is through such revelation that the awakening of humanity ignites. Joseph Gikatilla defined devekut as “the process by which man binds his soul to God by way of intellectual thought” (Hundert 290). In Judaism, the “Jewish soul first encounters the Divine through the study of Torah and Talmud. The traditional Jew knows God intellectually before he holds him emotionally” (Schmidt 105). As long as humanity remains ignorant of the divine Being, they will continue to strive in vain for spiritual growth and the evolution of human consciousness. By setting the mind on the emanations of God through sefirot, man can transform and elevate the human mind to its highest potential and state of being. This must be achieved by meditating on the emanations of the sefirot from the bottom up.

Gikatilla suggests that humankind can cleave to Shekinah. “If one arrives at Synagogue, Shekinah joins herself to him. Every day lived in accordance with Torah is woven into the souls” (Matt 24). When human beings observe the commandments of the Torah, Shekinah walks with them and never departs. Cleaving to God is an intimate and intentional act that begins to heal the cosmological split. “There is a task, a law, and a way: the task is redemption, the law, to do justice, to love mercy, and the way is the secret of being human and holy” (Heschel, I Asked For Wonder 108). Through embracing this knowledge, Israel and the entirety of humanity may derive strength and hope from the Torah, which provides them with a noble way of life that brings them closer to the presence of God. “The wife is the essence of the house, and when the house is corrected, the masculine and feminine are also corrected, and then the masculine comes to the Nukva, and they join together” (Laitman 216).

Being that Shekinah is the lowest sefirot and the opening to the divine, once the individual is within the divine presence, cleaving to Shekinah, “the sefirot are no longer an abstract theological system; they become a map of consciousness” (Matt 37). Entering into this dimension, a state of awareness that may be compared to a lower level of awakening, allows the individual to meditate on the characteristics of each sefirah as they ascend through levels of being in the divine presence. It is said that this path is not easy, the Divine Will can be harsh, and from the other side, the side of evil, demonic forces “threaten and seduce” (Matt 37). When the meditator reaches Binah, true awakening, she is called Teshuvah, Return. “The ego returns to the womb of being” (Matt 37). Once ascending to this level of the Divine sefirot, it is said that this state of experience cannot be known consciously, only absorbed. The individual is nourished from the sphere of Hokhmah, wisdom, and “beyond Hokhmah is the Nothingness of Keter, the Annihilation of thought” (Matt 37). In this ultimate sefirah, human consciousness expands and dissolves into infinity.

Works Cited

Dan, Joseph. Gershom Scholem and the Mystical Dimension of Jewish History. N.Y.U. Press, 1987.

Fishbane, Eitan P. “Mystical Contemplation and the Limits of the Mind: The Case of Sheqel Ha-Qodesh.” The Jewish Quarterly Review 93.1/2 (2002): 1-27. <https://doi.org/10.2307/1455483>. Accessed 14 September 2021.

Heschel, Abraham Joshua. I Asked For Wonder. The Crossroad Publishing Company, 2021.

—. Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1996.

Hundert, Gershon David. “Devekut, or communion with God.” Hundert, Gershon David. Essential Papers on Hasidism: Origins to Present. New York Press, 1991. 275-298.

Laitman, Michel. Abriendo el Zohar. Laitman Kabbalah Publishers., 2015.

Matt, Daniel Chanan. Zohar: The Book of Enlightenment. Paulist Press, 1983.

Novick, Lèah. On the Wings of Shekhinah. Theosophical Publishing House, 2008.

Schmidt, Gilya G. “Cleaving to God through the Ages: An Historical Analysis of the Jewish Concept of Devekut.” Mystics Quarterly 21.4 (1995): 103-120. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/20717258>. Accessed 14 September 2021.

Scholem, Gershom. Major Trends In Jewish Mysticism. Schocken Books Inc, 1946.

Tishby, Isaiah. The Wisdom Of The Zohar An Anthology of Texts. The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 1949.

Wolfson, Elliot R. “Hai Gaon’s Letter and Commentary on “‘Aleynu“: Further Evidence of Moses de León’s Pseudepigraphic Activity.” The Jewish Quarterly Review 81 (1991): 365-409. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1455325>. Accessed 05 September 2021.

—. The Book of the Pomegranate. Brown Judaic Studies, 2020.

Yohai, Shimon Bar, Moses De León and Michael Berg. The Zohar. Vols. 1-23. n.d. pdf. <z-lib.org>.