From lived experience to scientific research: normalizing a conversation that could protect every child.

Why I’m Writing This

I’m eight months pregnant with my fourth child, and one of my very real fears has been forgetting him in the car. Recently, I shared openly that I’ve forgotten a baby in the car before—twice, eight years apart.

The responses were not what I expected. While some offered compassion, others responded with judgment. That contrast made it clear to me why this story needs to be told more widely: to raise awareness, to replace silence with honesty, and to remind us that acknowledging the fallibility of the human mind is the first step to protecting our children.

My Story: Two Moments That Still Haunt Me

The first time, Mariyah was just a few weeks old. I had left my two-year-old with his grandmother and brought the baby with me, hoping she’d fall asleep in the car. By the time we arrived at the water department, she was sound asleep in the back seat, out of my view. Two weeks postpartum, exhausted, sleep-deprived, and cloudy, not yet used to the reality of carrying her in my arms after forty weeks of carrying her in my body, my habitual memory kicked in.

I parked, turned the car off, grabbed my bag from the passenger seat, and walked inside like I would any other day. I was standing in line for about five minutes when I saw another mother walk in with her baby. My stomach dropped. I ran out, horrified, and found Mariyah safe and still asleep in the car seat. The fear and guilt hit me so hard, I couldn’t hold back the tears. I felt like the worst mother ever. How could I forget this beautiful little girl was with me? I avoided going anywhere with her alone for months afterward.

The second time, Maximus was two. As we arrived at the funeral home for my uncle’s funeral, the kids spilled out of the car, loud and restless, darting in different directions. James was on one side trying to wrangle a few, and I was on the other gathering the rest. Without a word between us, I started walking in with the ones I had, leaving James behind with the others. In the rush, Maximus sat quietly buckled in, left behind amid the commotion. We both walked inside without him.

Just moments after entering, barely making it through the doors, a family friend walked over and asked about the baby. We looked at one another, realizing the other did not have him. I saw the same dawning horror on his face that I knew was etched into mine. Before I could catch my breath, without a word, he had already turned and was heading for the door. Maximus was safe, all smiles—but the memory still makes my chest tighten.

Both times, my children were fine. But the memories still live in me as reminders of how fragile the human mind can be.

Out of this awareness, I began taking precautions and posted what I believed was a simple, honest reflection—intended to show that these lapses are normal and to encourage expecting parents to protect against them. It was never about panic, but about proactivity: trusting research, trusting my own self-knowledge, and recognizing how easily the human mind can falter.

The Responses: Compassion and Judgment

What I didn’t expect was how polarizing the responses would be. A mother responded with compassion, sharing her own story of exhaustion and forgetfulness. Her honesty reflected the understanding that only comes from lived experience.

And then came the opposite. The family friend who had once asked about Maximus at the funeral home chose to weigh in, saying he couldn’t imagine how anyone could ever forget their child. That no matter how much was on a parent’s mind, there was simply no excuse. Seething with superiority, he says that it was something he has never done and would never do. He tried to cushion the blow with hollow praise, saying he had seen us do great things, that he respected us and knew we were intelligent people, but ended his comment by saying that he couldn’t feel sorry for people like this, and he was just shaking his head at my post. The contradiction was insulting.

The shame rose fast, searing and heavy, as my mind flashed to how others might read my words now—no longer as I meant them, but through the harsh filter of his judgment. What if they saw me as incompetent, careless? I wished I had stayed silent. Under that weight, I erased the evidence, deleting his comment as if it could undo the exposure.

But deleting his comment didn’t stop the ripple. Within minutes, two more notifications appeared. One read, ‘Oh hope they was free. Clips that is. .omgosh still WOW-ED.. C’MON NOW. SINCERELY.’ The other was nothing but an emoji of a man covering his face, captioned ‘oh wow.’

It wasn’t just one thoughtless remark—it was a steady drip of judgment, three separate comments, each one landing like another sting. The weight of them wasn’t in their length but in their insistence, a refusal to let the judgment go unsaid.

The audacity is staggering. A man—who has never carried a child, never endured postpartum fog, never juggled the relentless demands of caregiving and survival—felt entitled to lecture, to diminish, and to condemn. He didn’t just misunderstand; he dismissed. And in doing so, he revealed more about his arrogance than about my intelligence or my motherhood.

This is exactly why I’m writing. Because the silence forced by shame and judgment is dangerous

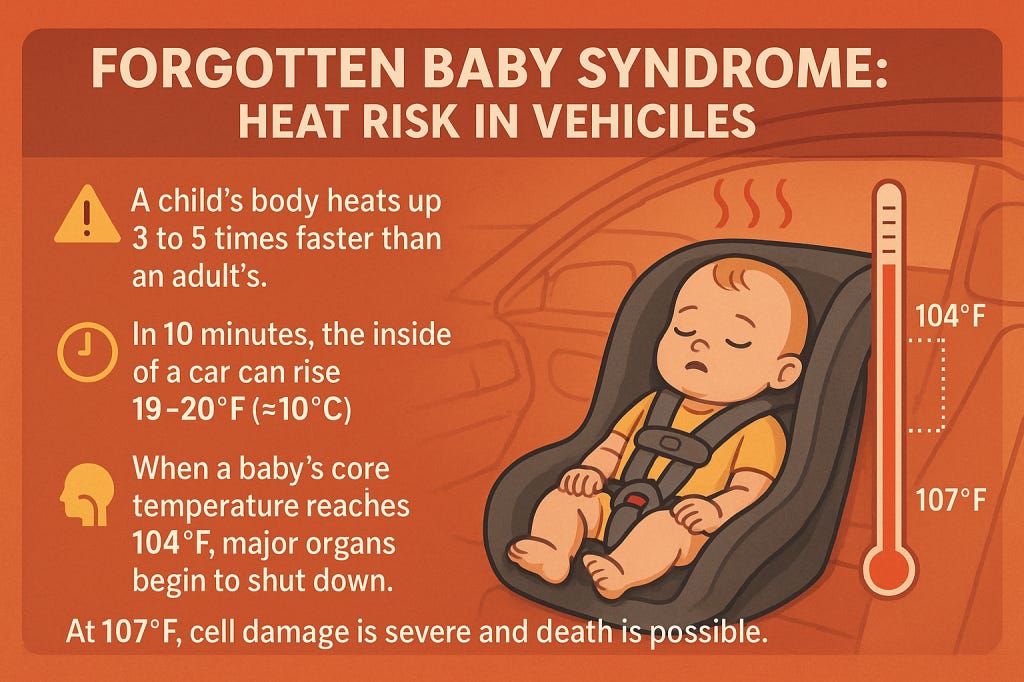

What the Science Says: Forgotten Baby Syndrome

Science offers clarity where judgment fails. What happened to me in both instances wasn’t about love or competence—it was about memory systems under strain. Researchers have studied this exact phenomenon and even given it a name—“forgotten baby syndrome.”

Here’s what researchers have uncovered about the brain mechanisms behind these lapses. What feels unimaginable is, in fact, a predictable neurological pattern.

- Prospective memory failure: This is the brain system that reminds us to “do something later.” Under stress, it can be overridden by habit memory (the brain’s autopilot). This is why a person can drive straight to work instead of to daycare without realizing it.

- Brain system conflict: Neuroscientists like David Diamond explain that habit memory (basal ganglia) can overpower prospective memory (hippocampus + prefrontal cortex) when stress, fatigue, or a shift in routine is present. This makes the phenomenon less about “forgetting” and more about one brain system literally overriding another. As Diamond puts it, this isn’t a lapse in love—it’s a tug-of-war in the brain, where habit can override intention under stress.

- Stress, fatigue, and routine changes: Sleep deprivation and high stress weaken prospective memory, but the risk rises sharply when routines shift. A different parent handling drop-off, a quick errand before work, or even a small change in the order of morning tasks can throw the brain off autopilot. Under these conditions, memory errors are most likely to occur.

- False memories: Some parents report vivid recollections of having completed the drop-off—an illusion created by habit memory. This makes the error not just a lapse, but a neurological misfire.

- Universality: Prospective memory failures happen across all kinds of tasks, even high-stakes ones. This is not negligence—it’s human fallibility.

- Perception vs. science: Public judgment blames individuals; neuroscience shows it’s a common and well-studied error.

- Scale of the issue: On average, 37 children a year die in the U.S. from vehicular heatstroke, with hundreds of deaths since the late 1990s.

These aren’t excuses; they’re explanations grounded in neuroscience. The truth is, it can happen to anyone. To deny that is to deny the reality of how the human mind actually works. Recognizing the science doesn’t remove responsibility, but it reframes the story from shame to understanding—and from blame to prevention.

Why Silence Is the Real Risk

The danger isn’t only the memory lapse—it’s the silence that follows shame. When parents are mocked or dismissed, they retreat. The instinct for self-protection kicks in, and instead of sharing their fears or experiences, they bury them.

That silence is dangerous for several reasons:

- It prevents awareness. If parents don’t feel safe admitting near-misses or fears, society never sees the scope of the problem. We’re left with the illusion that these incidents are rare or limited to “unfit” parents—when research shows they are a common human error rooted in how memory works.

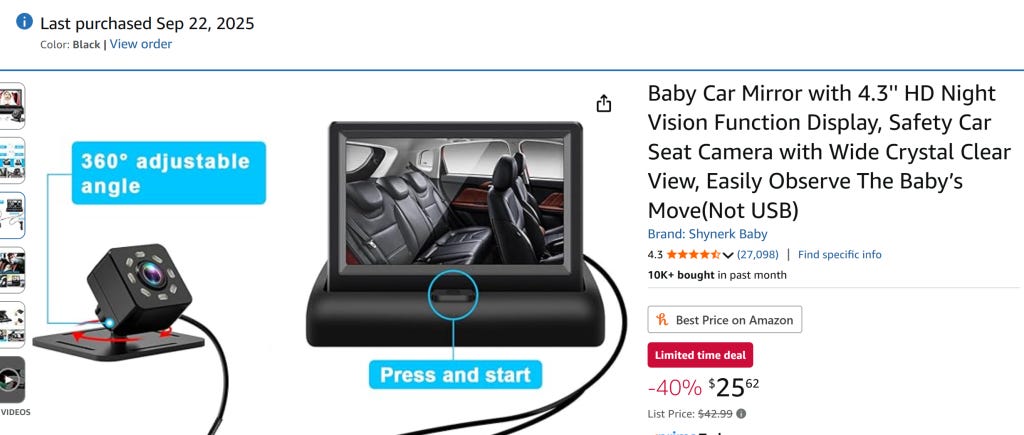

- It blocks prevention. Silence keeps us from normalizing the use of safeguards—reminders, car seat alarms, mirrors, door signs—that could save lives. Talking about these tools doesn’t reveal weakness; it teaches others what works. But people won’t share what helps them if they’re afraid of ridicule.

- It reinforces stigma. Shame creates a false hierarchy of “good parents” and “bad parents,” when the truth is that all parents are human. This stigma isolates the very people who most need support.

- It costs lives. Every child who dies in a hot car is not just the result of a memory lapse—it’s also the result of a culture that shames parents into silence instead of building systems of compassion, awareness, and prevention.

When we silence parents, we don’t just fail them—we fail their children. Empathy and openness save lives. Shame and judgment risk them.

Precautions You Can Take

Because forgetting can happen to anyone, prevention isn’t about paranoia—it’s about humility and love. Research and advocacy groups (like KidsAndCars.org) emphasize that since this is a predictable brain error, external reminders—clip systems, alarms, visual cues—are essential. Here are some precautions you can take (I’ll be linking to the items I’ve personally purchased):

- Built-in car alerts—many newer vehicles notify you to check the back seat, and some (like Tesla) have settings to keep the air running if motion is detected.

- Visual cues at home, such as a brightly colored sign on the front door, remind you to double-check before you go inside.

- Leaving an essential item in the back seat (your purse, phone, or even one shoe) so you’re forced to open the back door.

- Coordinating with daycare providers—ask them to call immediately if your child doesn’t arrive as scheduled.

- Setting phone reminders or alarms timed for drop-off.

- Talking openly with partners, family, or caregivers about routines, so responsibility is never assumed but communicated clearly.

These steps don’t suggest weakness—they acknowledge the reality of how memory works. Precautions empower us to act early, without shame, and build safety into daily life.

Closing Thoughts: From Judgment to Prevention

This conversation is not about labeling parents as “good” or “bad.” It’s about recognizing that memory lapses are a documented part of the human experience. Once we move away from framing it as personal failure and instead acknowledge it as a known risk of human cognition, we can advocate for early action without stigma.

When we normalize precautions, we empower all parents—even those who insist “it could never be me”—to protect their children. Awareness leads to safeguards, safeguards lead to prevention, and prevention saves lives.

A Call to Action

You can help normalize the reality of forgotten baby syndrome by starting open conversations with those in your life who are expecting or are new parents. Talking about the risk doesn’t plant fear—it builds awareness and saves lives.

Even something as simple as gifting a reminder device, mirror, or car seat camera at a baby shower can open meaningful dialogue. These gestures communicate that taking precautions is not a sign of weakness, but a natural and responsible part of caring for a child.

Together, we can replace silence with support, judgment with empathy, and fear with proactive love.

Leave a comment